Subscribe To The Moms Minute Newsletter - get the latest articles delivered straight to your inbox.

Friday, May 7, 2010

Your 6 Main Responsibilities As A Mom

1. Keep Your Children Safe.

This is the primary task during the early years. I’ve heard a child development expert say that your main job during the toddler and preschool years is to ‘stop them from killing themselves.’ In the first few years you have to worry about the dangers of drowning, sharp objects, poisoning, falling, stranger danger and so on.

In later years, you have to worry about keeping them away from drugs, alcohol, bad friends, and sexually transmitted diseases etc.

2. The second responsibility is giving your child the skills needed to live healthy, happy lives. This encompasses good nutrition, healthy living habits, exercise and forming good relationships with others.

3. The third important task of parenting is providing your child with the life-skills needed to succeed. This encompasses manners, reading, writing, cooking, laundry, balancing a checkbook and a host of other skills needed to function well in the modern world.

4. The fourth task that you need to perform in order to be an effective parent is to stay involved throughout all the different stages of childhood. From all animals, humans have the longest period of dependence. Parents need to be actively involved until kids have reached adulthood.

5. The fifth responsibility of effective parents is that you need to take care of yourself. You can’t care for your loved ones properly if you don’t make self-care a priority.

6. The sixth responsibility of effective parents is that you, not the kids, need to be in charge.

Sunday, April 18, 2010

Run Away Kids - When Your Child Is On The Streets & Wants To Come Home

Running Away Part II: "Mom, I Want to Come Home."

When Your Child is on the Streets

by James Lehman, MSW

In part two of this series on running away, James tells you how to handle it when your child is on the streets, and what to say when they come home—including giving them consequences for their actions.

In part two of this series on running away, James tells you how to handle it when your child is on the streets, and what to say when they come home—including giving them consequences for their actions.

For kids, running away is like taking a long, dangerous timeout. They may use it to avoid some difficulty at home, or to hide from something that’s embarrassing to them. You can also look at running away as a power struggle, because kids will often run instead of taking responsibility for their actions or complying with house rules. Above all, as a parent, what you don't want to do is give it power. That's the cardinal rule: do not give this behavior power.

The forces that drive your child to run are more powerful than the thought that he might get a consequence.

In the last article, I discussed what you can do before your child leaves, and how to create an atmosphere of acceptance at home. In part two, I’d like to talk about what you can do when your child is out on the streets, and how you should handle their re-entry back into home life.

WHAT TO DO WHILE YOUR CHILD IS ON THE STREET

Leave a Paper Trail

If your child has run away, you need to call the police, plain and simple. I understand that not all parents want to do this, but I think it’s imperative that you take this step. I can’t stress this enough: you want to have a written record that your child is not under your supervision, and that should be recorded at the police station. Also, if you call and report your child missing, know that your call will be recorded. I hate to say it, but one of the paradoxes for parents is that the authorities will often ask, “Why did you let your child run away?” when in fact, there's no way they can make them stay at home. Do your best to answer as honestly as you can, because it’s very important to document what’s happening. You should also call the Department of Human Services to create a paper trail there, too. They may very well tell you that they can’t give you any help, but the point is, you documented it. Be sure to write down the name of the case worker you talked to for future reference.

Should You Look for Your Child on the Streets?

I personally don’t believe in going and looking for your child on the streets if they are children who chronically run away. I don’t think you should give that kind of behavior a lot of power. The rules should be really clear in the family: “If you run away, you’ve got to make your way back here. I'm not going to come looking for you or call all your friends. If you're not home, I'll call the police.”

There are those parents who look for their kids to make sure they’re okay. I understand that impulse, but again, I don't think you want to give your child too much power or special status when they run away. If they get too much attention and too much power, you're just encouraging them to do it again the next time there's a problem. Unintentional reinforcement is something you have to be very careful about.

If you do find your child, you can say, “Look, when you're ready to come home, we'll talk about it.” I'm personally very leery about parents who chase after their kids and beg and plead. If you do beg them to come home, when your child comes back, they will have more power and you have less. From then on, whenever they want something or don’t want to be held accountable for their actions, they’ll play the runaway card.

The Sad Truth: Lack of Community Support for Parents of Runaways

Remember, it's your child’s responsibility to stay at home since you legally have no way to keep them there. In fact, I know of kids who’ve actually left while the police were there. They just said, “I'm not taking this anymore,” and they walked out. And the cops said to the parents, “We can't do anything until he commits a crime.”

In the states where I've lived, if your child runs away and you call the police, by law they can't do anything. Part of the obstacle that parents face is a lack of community support. Amazingly, there's no statute that requires kids to live in a safe place. That really puts parents in a bad place because society won't make your child stay at home or even in a shelter. When I was a kid, if you ran away from home they would take you to court and put you on probation; you were simply not allowed to run the streets and be a delinquent. Unfortunately, that law has changed. Today, it’s estimated that there are between one to three million kids on the street in this country. You have to wait 24 hours before you file a Missing Persons report—and even if you file the report, the police might find your child living on the street but they can't make him come home. Now your child is no longer a missing person, and you have even less power in some ways. When that happens, you just have to wait until your child wants to come home.

COMING HOME: RE-ENTRY AND FAMILY RULES

If Your Child Says They are Ready to Come Home…

If your child has dropped out of school and is abusing substances and living on the streets, I don’t think they should be allowed to come home without certain conditions. And if it’s decided that they can return, their re-entry to home life should be very structured.

I know it’s hard, but I think that even if your child is crying on the phone, what you want to get clear is, “We love you very much and you can come back again, but the rules aren't changing.” I've seen parents with abusive kids tell them very simply, “You can't come home until we have a meeting and agree to some rules. And until then, stay with your friends.” It’s difficult for parents to do, but I support that.

Have a Frank Discussion: What to Say When Your Child is Back Home

One of the main things you want to talk to your returning child about is what they’re going to do differently this time. Ask, “What’s going to be different about the way you solve your problems, and what are you going to do the next time you want to run away?” I recommend that you have a frank discussion with them. Let them know that running away is a problem that simply complicates their lives and makes their other problems worse. Again, we want running away to be viewed as a problem your child has to learn to deal with. We know as adults that once you start running from something, you may run for the rest of your life. Running away is one of the ways kids solve problems, it’s just not an effective way to do so. And in fact, most solutions that depend upon power and control are ineffective.

The Consequences for Running Away:

If your child has run away to avoid consequences, he should do them when he comes back—immediately. That's what he ran away from, and that’s what he needs to face. Running away is a very dangerous and risky behavior, and I believe there should be a consequence for it, as well. The consequence doesn't have to be too punitive; keep it task-oriented. One of the problems with consequences is that if they're not lesson-oriented, then the concept you’re trying to teach is lost. I like a consequence that says, “Write out the whole story of how you ran away. What were you thinking, what were you trying to accomplish? And then tell me what you're going to do differently next time.” Sit down with your child and get them to process it with you, and then talk about what your child can do differently next time together. Always hold them accountable. For kids who run away chronically, if you send them to their room, they won't learn anything. But if you ground them from electronics until they write an essay, make amends, and tell you how they’re going to handle it differently, eventually the behavior will change.

Here’s the truth: nobody ever stopped running away because they were afraid of punishment. Nobody ever said, “I'm not going to run away because the consequences are too severe.” If you’re a parent of teen who is in danger of running away, realize that the forces that drive him to run are more powerful than the thought that he might get a consequence.

Use Repetition and Rehearsal to Change Behavior

If your child writes an essay about why they ran away and tells you they are sorry, whether they mean it or not really doesn't matter. The important thing is that the learning is going to change. Think of it this way: if you had a spelling test every day, whether you tried or not, you're going to learn to spell. It’s the same way for your child—he has to write those words out. One of the primary ways kids learn is through repetition and rehearsal. Part of that, by the way, is giving them task-oriented consequences, over and over again. It’s much better to have your child write an apology five times than to send them to their room for five hours. Eventually, that learning will sink in—I’ve seen it happen time and time again.

Should You Ever Tell Your Child to Leave?

Sometimes kids come home and start falling into their old patterns of behavior. I know parents who have told their kids to go to a shelter or to go couch surf for a week. I am sympathetic to this approach, but I think there’s a very high risk involved; each family has to make decisions like these very seriously. If you're going to tell an under-age person to go couch surf, you have to think that through carefully. This is not because you’re going to be held criminally responsible or go to jail, but because bad things can happen—and you're going to have to live with the consequences, no matter what. Parents of girls often worry more because of the simple fact that it’s riskier for girls to run than for boys—more harm can come to them. Remember, each family has to live with its own decisions when it comes to safety—and there's no joking about that.

The Key to Dealing with Kids Who Run Away

In my opinion, the key to dealing with kids who run away both chronically and episodically is teaching them problem-solving skills, and identifying the triggers that lead to risky decisions. Kids have to learn coping skills that help them manage their responsibilities in the here and now, so they don't have anything to run away from in the future. That means doing their homework and chores, being honest and not lying about responsibilities and schoolwork, getting clean and sober if they have a substance abuse problem, and being able to face the music when they’ve done something wrong or publicly embarrassing. The bottom line is that kids need to learn how to take responsibility, be accountable, and not run away from consequences. Kids are not told enough that life is what you make it—and that means now, not when you're 25.

Running Away Part II: "Mom, I Want to Come Home." When Your Child is on the Streets reprinted with permission from Empowering Parents. For more information, visit www.empoweringparents.com

|

James Lehman is a behavioral therapist and the creator of The Total Transformation Program for parents. He has worked with troubled teens and children for three decades. James holds a Masters Degree in Social Work from Boston University. For more information, visit www.thetotaltransformation.com. |

Wednesday, April 14, 2010

You Don't Have To Be Perfect In Order To Be A Good Mom

You need to realize that perfection is an impossible and unrealistic goal. Blaming yourself and feeling guilty when things don't turn out as you anticipated is unhealthy and counterproductive.

Here are 5 simple truths you need to embrace in order to break the chains of blame and guilt.

1. Your children WILL have their share of challenges and problems, just like all kids do. They'll get hurt, fall ill, fight with their friends and have trouble at school. This is all part and parcel of childhood, and no matter how good a mom you are, there's very little you can do to prevent it.

2. From time to time, you will do things that will make your child angry, hurt or upset. It's all part of being human and your child will learn that life isn't always perfect.

3. Your child may have problems that you fail to recognize at the time.

4. There will be times when you get angry, irritated upset and exhausted, no matter how much you love your children.

5. You may have discovered later on that you've created serious problems for your child without meaning to. While you may regret this, beating yourself up over it is a senseless waste of time.

If you feel that you've caused your child pain and inadvertantly harmed her in some way, then ask your child for forgiveness and do what you can to make amends. And most importantly, forgive yourself.

Realize that you were doing your best with what you knew and now that you know better you can do better.

Saturday, April 10, 2010

What To Do When Your Child Is The Class Trouble-maker

Acting Out in School: When Your Child is the Class Troublemaker

by James Lehman, MSW

Every parent of an acting-out child knows that once your kid has a reputation for being a troublemaker at school, it's very difficult to undo that label. That’s because your child becomes the label; when the teacher looks at him, she often just sees a troublemaker. Sadly, it's very hard to change that image, because even when your child tries harder, the label is reinforced when he slips up. And then he's really in trouble, because not only is he still a troublemaker—now he's seen as a manipulator, too.

Every parent of an acting-out child knows that once your kid has a reputation for being a troublemaker at school, it's very difficult to undo that label. That’s because your child becomes the label; when the teacher looks at him, she often just sees a troublemaker. Sadly, it's very hard to change that image, because even when your child tries harder, the label is reinforced when he slips up. And then he's really in trouble, because not only is he still a troublemaker—now he's seen as a manipulator, too."It's your job to get along with your teacher, not your teacher's job to get along with you."

|

- How to Handle a Functional Problem

- How to Handle a Relational Problem

Acting Out in School: When Your Child is the Class Troublemaker reprinted with permission from Empowering Parents. For more information, visit www.empoweringparents.com

| James Lehman is a behavioral therapist and the creator of The Total Transformation Program for parents. He has worked with troubled teens and children for three decades. James holds a Masters Degree in Social Work from Boston University. For more information, visit www.thetotaltransformation.com. |

Sunday, April 4, 2010

Why Giving In To Your Demanding Child Is The Worst Thing You Can Do.

Are You Afraid of Your Acting-Out Child? Part I: Why Giving in is a Dead End

by James Lehman, MSW

Do you walk on eggshells around your child, afraid of doing anything to set him off? Do you appease him when you notice he’s winding up to throw a tantrum? In part one of a two-part series, James Lehman, MSW explains how fear of acting-out behavior sets up a dangerous pattern for your child—and the whole family.

Do you walk on eggshells around your child, afraid of doing anything to set him off? Do you appease him when you notice he’s winding up to throw a tantrum? In part one of a two-part series, James Lehman, MSW explains how fear of acting-out behavior sets up a dangerous pattern for your child—and the whole family."Now you’re negotiating on your child’s terms; your fear that he's going to act out is going to dictate how much you give in."

When a child is two or three, he learns to respond by saying “no” all the time. He starts resisting and asserting his individuality from his mother and father and often manages his anger and frustration by throwing temper tantrums. Some parents learn that you just have to wait those tantrums through, but others begin to worry that they're not able to manage their child or that they are not in control. Others worry that if they don’t give in—if they say “no” to their child—their child won’t love them anymore. In effect, these parents become afraid of their child’s acting-out behavior and are held hostage by it. They get worn down and often begin caving in to inappropriate demands as they try to appease their child instead of remaining firm and waiting the tantrum out.

If a child has successfully used inappropriate behavior at home, you will often see them trying it out at school. After all, if their strategy works on their parents, why shouldn’t it work on their teachers, too? In kindergarten and first grade if they don't get their way they may escalate. They may tantrum, call people names, throw things on the floor and walk around in the classroom when they’re supposed to be sitting down. It's important to note that for a significant number of children, the classroom structure that teachers utilize will be sufficient to change some of these behaviors.

Realize that if you have one child who controls the house with inappropriate behavior, this is not just your problem: it's also a problem for your other children. Make no mistake, dealing with an acting-out sibling can have a great and long-lasting influence on your other kids’ personalities. When siblings don’t know when, how or why their brother or sister is going to explode, it’s overwhelming and scary because they can’t control it. What often happens in these cases is that kids develop their own sub-type of Post Traumatic Stress Disorder. They will learn not to show their feelings. They may hide out in their rooms and submerge their emotions. That's because in their world, it's not safe for them to do so. It's not safe to show your feelings; it's not safe to say how you feel. After all, their sibling could explode and take it out on them at any given moment. So these kids wind up very flat emotionally; there seems to be no joy in their lives. There are things parents can do to correct these destructive patterns, but nonetheless, it's hard on everybody. [Editor’s note: for more on this topic, read James Lehman’s article, ”The Lost Children: When Behavior Problems Traumatize Siblings”.]

When parents used to come to me with this problem, I’d say, “We’re going to come up with a plan to change what’s happening in your house. Let's figure out some things for you to do when things get tough so you can empower and support yourself.” I think it’s nearly impossible for people to try to rely on willpower alone to change their parenting style. Here’s the truth: their child’s behavior wasn't going to change unless the parents’ behavior changed. I believe if you work at it, things will change; and if you don't, things will stay bad or get worse. The kid who's throwing a tantrum today is going to be throwing your chair across the room in ten years. And that's how he ups the ante as he gets older. Most kids escalate; it's a natural progression. They have to be more intimidating. When you're 13, it's very awkward to lie on the floor and throw a tantrum. It's much easier to throw something across the room and hit the wall. You see these kids punch holes in walls all the time; that is the evolution of their tantrum. Certainly as they get older, the intimidation becomes more real. There are kids who hit and push their parents. There are kids who intentionally break and damage things around the house. There are kids who hit their siblings or hurt them emotionally by calling them foul names. And make no mistake, this becomes a very real problem.

Are You Afraid of Your Acting-Out Child? Part I: Why Giving in is a Dead End reprinted with permission from Empowering Parents. For more information, visit www.empoweringparents.com

| James Lehman is a behavioral therapist and the creator of The Total Transformation Program for parents. He has worked with troubled teens and children for three decades. James holds a Masters Degree in Social Work from Boston University. For more information, visit www.thetotaltransformation.com. |

Sunday, March 28, 2010

Do You Know What Goes On In The Mind Of A Bully?

The Secret Life of Bullies: Why They Do It—and How to Stop Them

by James Lehman, MSW

Why do some kids turn to bullying? The answer is simple: it solves their social problems. After all, it's easier to bully somebody than to work things out, manage your emotions, and learn to solve problems. Bullying is the proverbial “easy way out,” and sadly, some kids take it.

Why do some kids turn to bullying? The answer is simple: it solves their social problems. After all, it's easier to bully somebody than to work things out, manage your emotions, and learn to solve problems. Bullying is the proverbial “easy way out,” and sadly, some kids take it.

Look at men who beat or intimidate their wives and scream at their kids. They’ve never learned to be effective spouses or parents. Instead, they're really bullies. And the other people in those families live in fear—fear that they're going to be yelled at, called names, or hit. Nothing has to be worked out, because the bully always gets his way. The chain of command has been established by force, and the whole mindset becomes, “If you'd only do what I say, there'd be peace around here.” So the bully's attitude is, “Give me my way or face my aggression.”

Aggression can either take the forms of violence or emotional abuse. I've seen many families that operate this way. I’m not just talking about the adults in the family, either—there are countless children who throw tantrums for the same reason: they’re saying, “Give me my way or face my behavior.” And if you as a parent don't start dealing with those tantrums early, your child may develop larger behavior problems as they grow older.

Ask yourself this question: How many passive bullies do you know? They usually control others through verbal abuse and insults and by making people feel small. They're very negative, critical people. The threat is always in the background that they're going to break something or call somebody names or hit someone if they are disagreed with. Realize that the behavior doesn't start when someone is in their teens—it usually begins when a child is five or six.

Portrait of a Bully

Bullying itself can come from a variety of sources. One source, as I mentioned, is bullying at home—maybe there are older siblings, extended family members or parents who use aggression or intimidation to get their way. I also think part of the development of bullying can stem from some type of undiagnosed or diagnosed learning disability which inhibits the child's ability to learn both social and problem-solving skills.

Make no mistake, kids use bullying primarily to replace the social skills they’re supposed to develop in grade school, middle school and high school. As children go through their developmental stages, they should be finding ways of working problems out and getting along with other people. This includes learning how to read social situations, make friends, and understand their social environment.

Bullies use aggression, and some use violence and verbal abuse, to supplant those skills. So in effect, they don't have to learn problem solving, because they just threaten the other kids. They don't have to learn how to work things out because they just push their classmates or call them names. They don't have to learn how to get along with other people—they just control them. The way they’re solving problems is through brute force and intimidation. So by the time that child reaches ten, bullying is pretty ingrained—it has become their natural response to any situation where they feel socially awkward, insecure, frightened, bored or embarrassed.

Here is what an aggressive bully often looks like: He doesn't know how to get along with other kids, so he's usually not trying to play with them. When you look out on the playground at recess, he's probably alone. He's not playing soccer or kickball with the other children; he’s roaming around the perimeter of all the interactions that take place at school on a daily basis. And whenever he's confronted with a problem or feels insecure, he takes that out on somebody else. He does this by putting somebody else down verbally or physically. A child who bullies might also throw or break things in order to feel better and more powerful about himself. When the bully feels powerless and afraid, he's much more likely to be aggressive, because that makes him feel powerful and in control. That’s a very seductive kind of thing for kids; it’s very hard for them to let go of that power.

Adolescents and Gang Mentality

When we talk about adolescent bullying, we're entering into another phenomenon altogether. The reality is that many adolescents in high school today are very abusive to each other. There are peer groups that will attack other kids verbally and emotionally, similar to a gang mentality. When these kids start calling other students rude names and questioning their sexuality, it is all done to dominate and bully them. If a teen or pre-teen doesn't want to be a victim, they have to join a group. The kids who don't socialize very well—the shy or passive types—often become the targets. And the threat of violence is always behind it. This trend in high school is prevalent today, and I think very destructive. In my opinion, parents and school administrators who ignore the way kids abuse each other in high school are kidding themselves. This behavior is hurtful and harmful, and there needs to be a lot more accountability.

Make no bones about it, bullying is traumatizing for kids who are the targets. In fact, I think children should be taught about bullying throughout grade school. They need to learn what it means, how to resolve it, and how to deal with a bully. If this is not taught, kids who are targets will think there's something wrong with them, and this vicious cycle—because that is truly what this is—perpetuates itself. Kids should also be learning how to handle their impulses and control themselves when they want to hit, hurt or intimidate others. Unless there's a concerted effort to deal with bullying and bullies in school, nothing will change. It's a challenge, but I firmly believe it can be done.

1. Teach Your Children about Bullying from an Early Age

I think from a very early age, you have to teach your child what a bully is. You can tell them the following (or even post these words in your house somewhere):

A bully is somebody who forces other people to do things they don't want to do.

A bully is somebody who hits other people.

A bully is someone who takes or breaks other people's property.

A bully is someone who calls other people names.

Then you have to set a standard that says, “We don't do that in our house.” Start that culture of accountability early. Teach them what the word means, and say, “You're accountable for that kind of behavior in our house.”

I think it’s also important that you talk about how to treat others. Ask your child, “How should you treat others?” And the answer is, “You treat others with respect ; if they don't respect you back, walk away. Treating someone with respect means not calling them names, threatening them, or hitting them.” You can also say, “You listen to others. You accept others. If they don't want to play with your toys or they don't want to share their things, you have to learn how to accept that.” This is not easy for kids, but they will learn. I really think children need to have the concept of bullying explained to them numerous times. That way, when any kind of bullying is going on, they can identify it and stop the behavior, both in themselves and others.

2. Create a Culture of Accountability in Your Home

I think the most important thing for every family is to have a Culture of Accountability in your home. This means your child is accountable to you: how he talks to you, how he talks to his siblings, how he treats his family members. When he’s bullying his siblings, don’t get sucked into his excuses; just because he had a bad day at school does not give him the right to mistreat anyone in your family, for example. Let me say it again: Your child is accountable to you.

When a bully feels powerless and afraid, he's much more likely to be aggressive, because that makes him feel powerful and in control.

Don't forget, bullies often have cognitive distortions—they see the world in a certain way that justifies their bullying. So you’ll frequently hear them blaming others and making excuses for their behavior. Most of the time, they really believe that stuff: they believe what they think, and that's what you've got to challenge. You can say directly, “It sounds like you’re blaming Jesse for the fact that you punched him. It is not Jesse’s fault that you hit him.”

Schools should also have a culture of accountability, and I think that many try. That's what detentions, suspensions and expulsions are all about—if your child breaks the rules, he should be held accountable, and it’s very important that you let him deal with the natural consequences and not try to shield him.

3. The Skills Your Child Needs to Learn

Plain and simple, a child who bullies needs to learn how to solve social problems and deal with their emotions without acting out behaviorally. Have conversations with your child where you ask, “What happens when other kids don't want to play your games? What do you do? What do you do when other kids have things you want and they won't give them to you? How do you handle that? How do you handle it when you think you're right and they're wrong and there's nothing you can do about it?”

Your child has to learn how to resolve conflicts and manage his emotions. He needs to learn the skills of compromise, how to sacrifice, how to share and how to deal with injustice. He should also learn how to check things out, and to ask himself, “Is what I'm seeing really happening? Does Jonathon really hate me, or is he just in a bad mood today?”

Kids have got to learn how to manage their impulses. If their impulse is to hit or to hurt or call someone names, they have to learn to deal with that in an appropriate way. Many children and adolescents have the impulse to hurt others—they have impulses to do all kinds of things. But they need to learn to handle them, and kids who bully are no exception.

4. What to Do If Your Child is Bullying Others in School

Kids who are bullying others should be held accountable at home—they should absolutely be given consequences for their behavior. And the consequences should go like this: your child should be deprived of doing something he or she likes. So, no TV or computer games or cell phone, for example. And they also should have to do a task: they should write an essay or letter on what they're going to do next time they're in the same situation or feel the same way—instead of bullying. It’s critical that they start thinking of other ways they can solve this problem. Understand that they may not have any ideas, and that’s where you have to interact with them and coach them as a parent. In the Total Transformation Program, there's an interview process I outline where parents learn to talk with their children to solve problems, rather than explore emotions and listen to excuses. If your child is hurting or bullying others, he needs to have conversations that solve problems. He does not need or benefit from conversations that explore emotions. Bullies tend to see themselves as victims, so the conversation has to focus on them taking responsibility for their behavior.

I think your child's teachers should handle the process of having your child make amends for his behavior at school. But remember that bullies don't stop bullying when they get home—they often target younger or weaker siblings. You have to be very clear if your child is bullying—be very black and white; leave no gray areas. Don't forget, your child is bullying because solving problems— talking to people and working things out—is very hard for him. Again, your child is taking the easy way out. We all go through the growing pains of learning how to negotiate in social situations—in fact, we may work on this skill our whole lives. There should be no exceptions for anyone in your family when it comes to these skills. For a child who is using bullying as a shortcut instead of developing these skills, you have to work even harder as a parent to coach them on what to do.

When Bullies Grow Up

Make no mistake, if a child bullies, that tendency can stay with them their whole lives. Fortunately, some bullies do mature after they leave school. You'll see them get into their early twenties and go their own way; they get married, they go to college, they start a career, and they stop their bullying behavior.

But sadly, you will also see young child bullies who become teenage bullies and then adult bullies. How does this behavior and lack of social skills affect them? These are the people who abuse their wives and kids emotionally and sometimes physically. These are the people who call their spouses and kids names if they don't do things the way they want them to. Bullies may also become criminals. Look at it this way: a bully is somebody who is willing to use aggression, verbal abuse, property destruction or even violence to get his way. An anti-social personality disorder (which is how criminals are classified) refers to somebody who is willing to use aggression and violence to get his way. The criminal population is literally full of bullies who, among other things, never learned how to resolve conflicts and behave appropriately in social situations.

If you think your child is bullying others, it’s very important to start working with him now. This behavior is already hurting his life—and will continue to do so if it’s left to fester. If you expect your child to “outgrow” bullying once he reaches adulthood, realize that you’re also taking the risk that he may not—and that choice may negatively affect him for the rest of his life.

The Secret Life of Bullies: Why They Do It—and How to Stop Them reprinted with permission from Empowering Parents. For more information, visit www.empoweringparents.com

|

James Lehman is a behavioral therapist and the creator of The Total Transformation Program for parents. He has worked with troubled teens and children for three decades. James holds a Masters Degree in Social Work from Boston University. For more information, visit www.thetotaltransformation.com. |

Thursday, March 18, 2010

Does Your Child Think He's The Boss?

"My Child Thinks He's the Boss!"

How to Get Back Control of Your Home

by James Lehman, MSW

Why do some kids try to become the so-called “alpha dogs” of their families? The answer lies in an old saying: Nature abhors a vacuum. And in my experience, if there's a vacuum of power in a family, somebody's going to try to fill it.

Why do some kids try to become the so-called “alpha dogs” of their families? The answer lies in an old saying: Nature abhors a vacuum. And in my experience, if there's a vacuum of power in a family, somebody's going to try to fill it.

Understand that some mature, older kids do gain some authority in their families, and that’s natural. In fact, it works well when you have a very responsible, “adultified” child. Often, the oldest child in a family will take on a leadership role among his siblings. And when that child has a pretty good balance of behavior, he will try to follow through on house rules; his behavior usually won’t pose a problem.

“But if your child does something inappropriate and you don't give him any consequences, you're really going to look powerless.”

But if a child doesn't have that balance or maturity, or if the parents aren’t clearly in control of the family structure, it’s another story altogether. Some kids will start to compete with their parents for power from an early age. Instead of following through on the adults’ wishes, they’ll be more interested in controlling their siblings and calling all the shots in the house. In other words, they will start filling that vacuum.

Sometimes the vacuum in parental authority exists because of work and school schedules. In families today where both parents often work, there are frequently times when kids are left under the care of older siblings. A gap is then created which a certain kind of child will fill. And if the child has his own negative intentions, he’ll have plenty of time without adult supervision to intimidate and manipulate the other kids in the family. He will use this time to go against his parents’ wishes and play the big shot. He might give his younger siblings ice cream after school, for example, even though it’s against the rules. Or he may intimidate them when it’s their turn to go on the computer, so he can stay on as long as he wants. And when you get home, if his younger siblings tattle on this child, he’ll get them back the next day. This means that for the other children in your family, there is no safety. It becomes very easy for your dominant child to control the family from here on out.

Parents are often initially afraid to stand up to a child who’s bossing everyone around. This might be because there’s been a parenting gap all the while, or because they depend on this child to supervise the other kids when they’re gone. But if they avoid talking to their dominant child about this, they will soon see a shift in the balance of power. At some point, their younger kids will surmise that the adults cannot protect them from their “bossy” sibling. Once the younger kids believe they aren’t safe, then they have to make their own separate deals with that sibling. And that deal usually involves giving in to him and following his lead.

When this happens, you’ll see all kinds of inappropriate behavior begin to blossom and thrive. Sometimes these “alpha dog” kids are funny, so they become clowns and make unkind jokes at their parents’ expense. By the way, I'm not talking about a child who makes a harmless joke, I'm talking about one who will put his parents down and make demeaning comments about them. His siblings laugh at those jokes because they're more afraid of his power than they are of their parents’ authority. And why shouldn’t they be? When this dynamic is controlling a family, the dominant child is much more powerful and has a greater impact on their lives than the parents do.

As things build to a head, the parents feel less and less in control and more and more perplexed and overwhelmed by what’s happening. Often, they are not really sure what to do. A family in this situation has really hit a level where they aren’t functioning in a healthy way anymore.

If I had the parents of this kind of bossy or dominant child in my office, I would say, “Maybe you can help what’s happening right now and maybe you can't, but let's get one thing clear: your child’s goal is to have power and control. And because of the makeup of his personality, he’s using that power and control to be negative. He’s using it to undermine you, to intimidate his siblings, and to be disrespectful toward you. He has an opportunity, and he's using it to make himself feel better and stronger.”

I would then sit down with them and come up with a plan to help them take the power out of their child’s hands and put it back into theirs—where it belongs in any healthy family structure.

How to Take Back Power from a Child Who Thinks He’s the Boss

Have Clear Expectations of Your Child and Hold Him Accountable

You have to set limits on any child who is trying to run the family and hold him accountable. Parents are afraid that if they say, “Go to your room,” their dominant child will say, “Screw you!” So those parents might think they’ll look powerless in front of their other kids when this child refuses to comply.

But here’s the rub: If your other kids see you direct your child to his room and he refuses, they know that their brother has the problem. Conversely, if your child does something inappropriate and you don't give him any consequences, you're really going to look powerless. In other words, if you tell him to go to his room and he says “No, I'm not going—and you can't make me,” you actually look powerful to your other kids. Your acting-out child looks primitive and wrong when he defies you. The other kids know where he's supposed to go, and even if he refuses, they still see you being the parent.

If you try to avoid a scene because you're afraid you're going to lose face, what tends to happen is that your child will slowly gain more and more power, and that will be confusing to your younger kids. I’ve found that the gut reactions of many parents in this situation are often wrong. They might think, “We'll let him slide this time; we'll just negotiate with him later.” But they're negotiating with the wrong person, because what this child wants more than anything is to maintain power and control—and unfortunately, his parents are handing it to him on a platter.

Make no mistake, if your child is using power to solve relational, social or functional problems, he will never be able to get enough. This is because he’s being driven by insecurities and fears. There's just not enough that you as a parent can ever give him—so your child will simply continue to challenge you more and more.

To Get Back Parental Authority, Get Control of Your Bossy Child First

If you want to get control back over all your children, you have to first get control of your dominant child. Even though your other kids may be acting out as well, your “alpha dog” kid is causing the imbalance in authority; consequently, he is the one you have to manage. While naturally you have to hold your other children accountable for their actions too, your priority right now is to address the behavior of your dominant child. That means that you have to give him consequences that he can't undermine--and then you need to be firm and follow through on them.

I also want to make a very important point here: when your younger kids act out, don't make excuses for their behavior. Don’t let them off the hook by saying “Oh, they're under a bad influence.” It's easy for parents to see the younger kids in the family as victims. But don't forget, just because you're a victim doesn't mean you get to break the law. You have to hold your other kids accountable for their behavior, too. If they protest and say, “But Michael's doing it,” you can reply, “We're dealing with Michael. But know that when you break the rules, there are going to be consequences.”

Change the Routine

If your alpha dog child uses after school time to take over the house, change the routine. That might mean he’ll go to somebody else's house when school gets out, where he will be supervised by an adult—or it might mean that your other kids will go elsewhere. The point is, if his controlling, bossy behavior is occurring around a certain time of day or in certain situations, work to break out of the pattern by changing things up. Limits have to be set, and this is often a good place to start if you can manage to do so.

Don’t Over-negotiate with Your Child

If you over-negotiate with a child who’s trying to be the boss, you're giving him the message that he's your equal. In my opinion, that's not a good message for a child or adolescent to have who is already acting out. Soon he’ll start bargaining with you in order to behave appropriately. And believe me, there's a big difference between motivating kids with a reward system versus bargaining with them. I think when you’re bargaining with your child, he’s often wearing you down until you give in. You end up saying, “Okay, as long as you behave, you can have your way.” In contrast, when you're rewarding someone, it's clear that you're the one with the authority giving out the reward. Bargaining with your child isn’t effective because you’re still not in control in the way that you need to be with him.

Write up a Contract with Your Child

I don’t believe contracts are magic wands. But I do believe that if everybody understands what the game is and what the rules are, the chances of your child following those rules increase. In my experience working with kids, I’ve also found that if something is written down on paper, it becomes more real to them.

So sit down and draw up a contract with your child that clearly defines what he has to do in certain key areas. It should state that if he complies with the contract, he will be rewarded—and it should specifically outline what those rewards will be. It should also be very clear what the consequences will be for competing with you as a parent.

Here’s how that would play out. If your child is disrespectful and he's told go to his room, as long as he complies, the matter is settled. The protocol once he gets to his room might be that he needs to stay there ten minutes, calm down, and talk to you about what he's going to do differently next time. But if he refuses anywhere along the line, that's when the consequences set in. If he starts to act out, you can say, “This is in our contract, and you agreed to it. Now hand me your iPod.” Remember, as kids get older, they want more sophisticated privileges and rewards. Going to school dances, going to parties, or driving the car are some examples. Use these for leverage.

Expect Some Pushback

You should expect your child to react really strongly to the new structure you impose as soon as you establish it. Adolescents do not give up power easily. Your family may even go through some chaos for a time as your child fights against you. But you have to make that value judgment. Ask yourself, “Is it worth living like this, or is it worth going through some chaos for awhile to correct the situation?” Personally, I think parents have a responsibility to protect all their kids. And they need to protect them from everybody, including from each other—and from themselves.

Appeal to Your Child’s Sense of Maturity in a Positive Way

I think it’s good to reward positive behavior in your child whenever you see it. Use that hypodermic affection by saying, “Hey, I noticed you talking nicely to your little brother today. Good job.” You can build in some incentives by saying, “We know you want to feel like an older brother. So if you follow this plan, you can stay up an hour later than the other kids. You can watch TV and have the computer to yourself during that hour, but this is the way you have to act.” Use the carrot and the stick. There is nothing wrong with rewarding appropriate behavior.

Parents Need to Get on the Same Page

I think it's important for parents to come up with a game plan that outlines how they’ll deal with their children. It should be a plan they're both comfortable with. Parents have to meet and get clear about their message before presenting it to their kids. So if one parent tends to say things like, “Look, Will can't help it, he has ADHD,” but the other parent says, “No, he's responsible for his behavior just like the other kids are,” they'd better get that settled behind closed doors—or at least, they should know where they stand.

Two parents who can't get on the same page about how to hold their kids accountable can easily create that vacuum in power which their acting-out child will only be too happy to fill.

Advice for Single Moms and Dads

If you're a single parent, I think it’s important for you to keep the expectations for appropriate behavior very clear. In my opinion, all the kids should do more in a single parent family. They should have more responsibilities in general, and they should pitch in and help out. Often, there is an older child who has more responsibility, and I think in any family system, those who have more responsibility should have more rewards.

But if you’re a single parent and one of your children begins getting into power struggles with you, you have to set limits very clearly on their behavior. Talk with your child very frankly about it. You can say, “You're a big help to me, but you're not my co-parent. And because you're a big help, I try to let you do some things on your own. I’m trying to be flexible with you. But remember, I'm the parent—and you're the child.”

"My Child Thinks He's the Boss!"

How to Get Back Control of Your Home reprinted with permission from Empowering Parents. For more information, visit www.empoweringparents.com

| James Lehman is a behavioral therapist and the creator of The Total Transformation Program for parents. He has worked with troubled teens and children for three decades. James holds a Masters Degree in Social Work from Boston University. For more information, visit www.thetotaltransformation.com. |

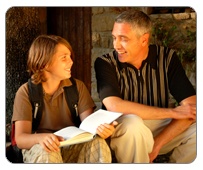

Monday, March 8, 2010

Creating A Culture of Accountability In Your Home

How to Create a Culture of Accountability in Your Home

by Megan Devine, Parental Support Line Advisor

The father's voice on the other end of the Parental Support Line sounded exhausted and overwhelmed when he said, "I know you told me that I have to hold my child accountable, but what exactly does that mean?”

The father's voice on the other end of the Parental Support Line sounded exhausted and overwhelmed when he said, "I know you told me that I have to hold my child accountable, but what exactly does that mean?”

It’s an excellent question, and one that we receive often on the Support Line. You’ve probably noticed that we talk a lot about “accountability” in Empowering Parents, as well. But have you ever wondered what it really means to hold your child accountable?

It's never too early—and it's never too late—to start a Culture of Accountability in your home.

I think it’s often helpful for parents to break big concepts down into bite-sized pieces in order to fully understand them. The word “accountable” itself means responsible, or taking responsibility for one’s actions. So when we’re talking about our kids, the question becomes, how will you make sure your child accounts for his or her actions? In other words, how will your child take responsibility for their behavior after the fact? And how can we help them think about that responsibility before they behave inappropriately?

Remember, we want to promote a system of responsibility and accountability for actions in our home. James Lehman calls it a “Culture of Accountability,”and it means that each member of the family is responsible for their own actions and behaviors, each person is responsible for following rules and expectations, and each is responsible for how they respond to stressful or frustrating situations. The simple truth is that most kids, and even some grown-ups, don’t take responsibility for their actions. Without accountability in place, kids blame others for their actions, refuse to follow rules they find unfair, and find ways to justify their behavior. For example, if your child breaks the house rules by calling his siblings rude names or being physically aggressive with them, he may be in the habit of blaming his brother or sister for his verbal abuse. You’ll hear things like “She wouldn’t get off the computer and I wanted to use it!” or “He wouldn’t move, so I pushed him.”

Understand this: when you have created a Culture of Accountability in your home, your child will know that no matter who started it or what happened first, everyone is responsible for their own behavior, and everyone has to follow the rules. Just because he was using the computer doesn’t mean he can call his sister foul names because blaming someone else doesn’t change the rules. As James says, “there is no excuse for abuse, period.”

Giving consequences and sticking to them is another important piece of the accountability puzzle: your child should know that if he chooses to break the rules, there will be a consequence for that choice. The bottom line is that no one in the family should get away with changing the rules to fit their needs or feelings.

Let me use an example from the work world. Let’s say it’s your job to make sure that a shipment of light bulbs arrives safely at their destination, but you were preoccupied and did not check the shipping boxes, and many of the light bulbs arrived damaged and broken. Your boss will likely hold you accountable for the breakage. You may not like it, but it is your job to meet those expectations—and if you don’t meet them, you won’t get paid. You can’t blame it on someone else, as it was your responsibility to check the boxes. Since your job’s Culture of Accountability says that you’re in charge of the light bulbs, you understand that you need to take responsibility for what happened. You may have to discuss what went wrong, and explain how you will make sure to do it differently next time—and you will probably have to work a little longer that day to fix the problem. That’s the heart of what it means to be responsible.

This is similar to what James is talking about when he says you need to hold your children accountable. You have rules and expectations for your child, and they are responsible for following those rules. If they don’t follow them, they do not get “paid” with the privileges and rewards they value. Again, blaming others or acting inappropriately does not relieve them of their responsibility to meet the expectations of the family.

You might be thinking “I know my child is responsible for meeting our expectations and following our rules, but how do I hold him accountable when he doesn’t want to be?” Remember, as James often says, you can’t get your child to want to do something he doesn’t want to do. You can, however, use effective parenting strategies in combination with rewards and consequences to get hold child accountable.

How to Be Clear about Expectations and Set Clear Limits

If you have a rule in your home of no name calling, here’s how you can set clear expectations and limits around it. Let your child know the following: “In this house, we don’t call people names. It doesn’t matter if someone makes you really angry, or if they started it. Each person is responsible for following the rules. If you call someone else names—remember, it doesn’t matter who started it—you will lose some of your game time today.”

Kids will often try to shift the focus to someone else. If this happens, you can say, “It sounds like you’re blaming your brother for the fact that you called him names.” Be sure all members of the family know that putting the blame on someone else will no longer be acceptable. In a Culture of Accountability, each person is responsible for their own actions, and for following the rules, no matter what someone else does. Be clear about the rules, and what each person can expect to see happen if they choose not to follow those rules.

Talk to Your Child and Help Them Figure out How They Will Follow the Rules

It isn’t enough to simply say “don’t do that;” kids often need to know what they can do, not just what they can’t do. Help them problem solve. Ask your acting-out child, “What can you do to help meet our rules and expectations?” Remember, it doesn’t matter if they think the expectations are fair or not; they simply need to take responsibility for meeting them. Remind your child: “It’s your responsibility to control your temper. Just because your brother is bothering you does not mean you can push him. If your brother is annoying you, and you’re tempted to call him names, what can you do instead?” You might have your child write down a list of the things they can do to help themselves follow the rules when they are tempted to break them.

Use Cueing

Once your children have come up with ways they will help themselves follow the rules, you can use what James calls “cueing” – giving a reminder of what is expected. When you hear your child start to get annoyed, you might say, “Remember what we’ve been talking about. You are responsible for following the rules. Why don’t you go check your list of things that you’re going to do when you’re having trouble following the rules?” To help create that Culture of Accountability for everyone, you might also consider posting the family rules in a public area in your home, like the refrigerator door.

Use Consequences to Hold Your Child Accountable

Once you have clarified the rules and helped your child come up with some ideas on how he might behave, let him know what he can expect to see happen if he still chooses to break the rules. Remember, tie the consequences to your child’s behavior, and keep them short-term. For example, let your child know, “If you choose to call your brother names, you will lose access to your electronics until you can speak appropriately for two hours.” Be sure to follow through with the consequences you set; remember, without clear consequences, there is no real incentive for your child to become accountable.

The good news is that creating a Culture of Accountability is a very reachable goal for parents. In fact, effective parenting helps your child learn to be accountable—to both accept responsibility for meeting the expectations of your family, and to develop the skills they need to meet those expectations. And when all the members of your family start becoming accountable to each other, your kids will have a clear understanding of the rules and will be much more motivated to uphold them. You will even see your kids trying to follow the rules when they don’t want to do so, because they will know that they will be held responsible for their choices, no matter how they feel or what excuses they give you.

Realize that when you first try to put the Culture of Accountability into place in your home, your kids may fail to meet their responsibilities, even with clear limits and good problem solving techniques. It will take practice to help them understand that they will be held accountable for their actions. But as James says, “parents are the solution, not the problem.” You can teach your children the skills they need to take responsibility in their lives now, and for their future. With consistency and practice, your kids will learn that they are responsible for their actions and behaviors. It’s never too early—and it’s never too late—to start a Culture of Accountability in your home.

How to Create a Culture of Accountability in Your Home reprinted with permission from Empowering Parents. For more information, visit www.empoweringparents.com

| Megan Devine is a Parental Support Line Specialist and writer. She holds a Master of Fine Arts degree from Goddard College. She has a children’s career book in pre-publication, and has several other books in the works. |